How I over-engineered my Home Kubernetes Cluster: part 2

Introduction

In my previous post, I went over the setup of a 2-node Kubernetes cluster using Raspberry Pi. I explained how I set up the cluster, how I exposed it to the internet, and how I set up storage. In this post I will address the rest of the setup, which includes the monitoring and alerting, the services and the backup and disaster recovery strategy.

Once again, you can find the full setup in my GitHub repository.

Contents

In the previous post…

1. The cluster setup

2. Ingress

3. Storage

In this post:

Monitoring was something I wanted to set up from the beginning. I wanted to be able to see the status of the cluster and the services running on it. Also, I wanted to be able to get notified if something went wrong, that way I can react quickly and fix the issue.

I think that monitoring is also crucial for security. It allows you to get a general overview of what is going on, notice if someone is calling your services a lot, know if people are trying to brute force your services, …

I went with a basic Grafana + Prometheus + Loki setup for dashboards, metrics and logs respectively. I really like Grafana’s software so I chose it to be able to dive deeper and understand it a bit more.

Prometheus

The basic setup is quite simple. First of all I used the Prometheus helm chart with a few simple configurations which you can find at the repo. I configured the retention time and size and the storage class and size. I also added an ingress resource to expose Prometheus to the internet using basic auth, in case I want to check something when I’m not at home. I feel quite safe with this setup since I also set up alerts for when people try to brute force password on the cluster.

Prometheus will be in charge of scraping metrics from my services and allowing Grafana to do queries on them so it can draw some nice graphs.

Grafana

I also set up Grafana with the official helm chart. The configuration for Grafana is a bit more complicated. First of all, I had to create a postgres database in which to store the data. I created a simple PostgreSQL deployment which will serve as storage for all the services I have which require a database. Then, I had to configure multiple things. For example, I configured the password using a secret which needs to be mounted as a file so the Grafana configuration can read it. I also configured the data source for Prometheus, and the database credentials for Grafana. All in all, the setup is kept minimal. Finally, of course, I exposed Grafana to the internet so I can check my beautiful dashboards from anywhere.

Grafana is in charge of querying the different data sources (Prometheus and Loki in this case) and making dashboards out of their data, as well as sending alerts when something goes wrong. I configured it to send alerts to a Telegram group using a bot, that way I can receive alerts on any device and react to them easily.

Loki and Promtail

The Loki configuration is the most complex of the three because I did it from scratch.

Let’s start from the building block, Promtail. Promtail is in charge of reading the logs of all the pods in the cluster and sending them to Loki. There should be a Promtail instance in every node of the cluster. To do this I used a DaemonSet, which will ensure that every node has an instance running. Promtail has access to the folders where the logs are found, and also has a file in which it keeps track of the logs it has read in every pod. It is set up to send the logs it gathers to the Loki push gateway, which we will configure later.

Promtail is set up with 2 different configurations. The first one, called pod-logs is the main one. It finds all the pods in the node using the Kubernetes API and gathers their logs. It also adds some labels like the namespace and pod name.

The second one, called ingress-nginx-metrics is a more complex one. It only checks logs from the ingress-nginx namespace, and it doesn’t send them to Loki as the other job is already doing so. Instead, it parses the logs, which are in json format thanks to our ingress-nginx configuration which I described in the first part of the blog post. Then, it exposes metrics using the Promtail metrics action.

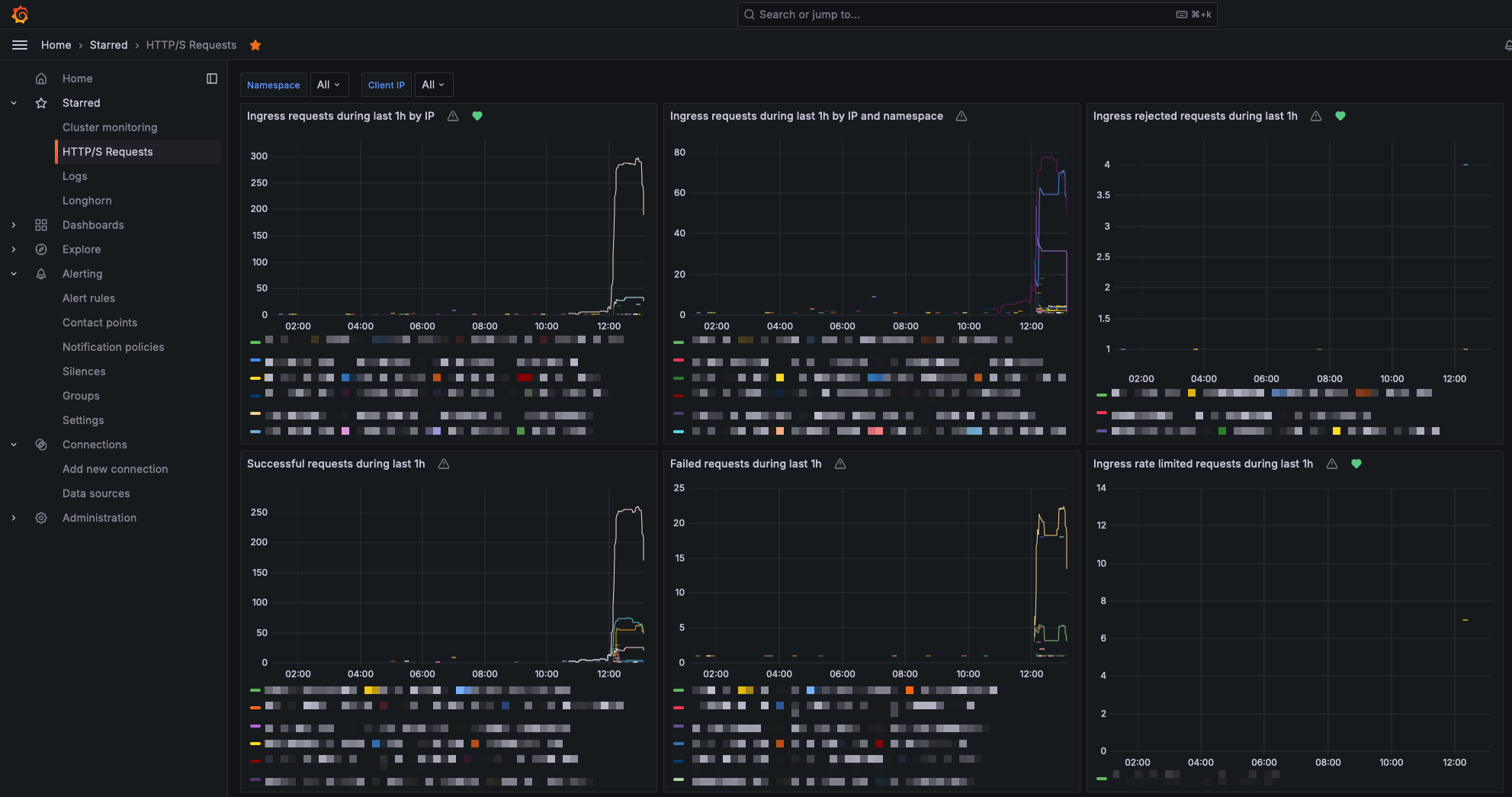

I created different metrics which expose different information. For example, http_requests_total_ip has a label for client IP, and http_requests_total_ip_namespace_status has labels for client IP, ingress namespace and status code. By having different metrics which expose different sets of labels, I am able to keep cardinality minimal for each metric, which will yield more accurate queries later.

For example, if a client IP called the Grafana ingress once, and the Prometheus ingress another time, having a query which shows the increase of requests per client IP using the http_requests_total_ip_namespace_status metric will result in 2 different series with increase 0, which will sum to 0. If, instead, I use a metric with only the client IP label like http_requests_total_ip, the query will show an increase of 1, since the change from no data to 1 is accounted as 0.

Although this innacuracy is not very important for bigger setups with a greater number of requests, it allows me to not miss clients which call my services very few times.

Another thing which I mentioned on my first post is geolocalization of IPs. For this I used the geoip parsing stage of Promtail, which uses a MaxMind database file to add geolocation data to metrics. This way I can have map visualizations in Grafana. To set it up, I just used the geoipupdate Docker container from MaxMind in a DaemonSet deployment, which updated the database file every day in every node, and I then shared the database folder with Promtail. You can find the exact configuration on the repo.

After having Promtail set up, I had to set up Loki. Its configuration was quite simple, I just created a deployment, which in this case I tied to a specific node, and used local persistent volumes. It would also work using Longhorn, but this time I used this setup as I didn’t care about backing up this data and wanted to keep it simple.

Configuration and dashboards

At this point we have Loki, Prometheus and Grafana set up. The only things left to do is, first of all, add the Loki data source to Grafana, and then decide which services should be scraped with Prometheus.

Prometheus scrape configuration is really simple. By default, Prometheus has a pipeline configured to scrape metrics based on pod annotations. To scrape a pod we just need to add a few annotations:

prometheus.io/scrape: "true": This tells Prometheus to scrape the pod.prometheus.io/port: "8080": This tells Prometheus which port to scrape. It only needed when the pod has multiple ports, otherwise Prometheus will scrape the first one.prometheus.io/path: "/metrics": This tells Prometheus which path to scrape. It is only needed when the pod has a metrics path different from/metrics.

After setting up the proper annotations, Prometheus will auto-discover the pods and start scraping them.

After this, its just a matter of creating dashboards in Grafana. For example, using the custom Promtail metrics, I created a dashboard to show the increase in calls by client IP using this query:

sum by(client_ip) (

increase(promtail_custom_http_requests_total_ip{}[1h]) > 0

or

last_over_time(promtail_custom_http_requests_total_ip{}[5m])

) > 0

I added the last_over_time function to the query to show the client IPs which called the service just once, as otherwise they showed up in the graph as 0 in a single point. This way they have their real value and appear for 5 minutes after the call.

Once you have all the dashboard you want set up, you should set up some alerts. For example, I have alerts when a given IP is calling my services a lot, when a pod is restarting too much, when there are a lot of forbidden requests (blocked by WAF), …

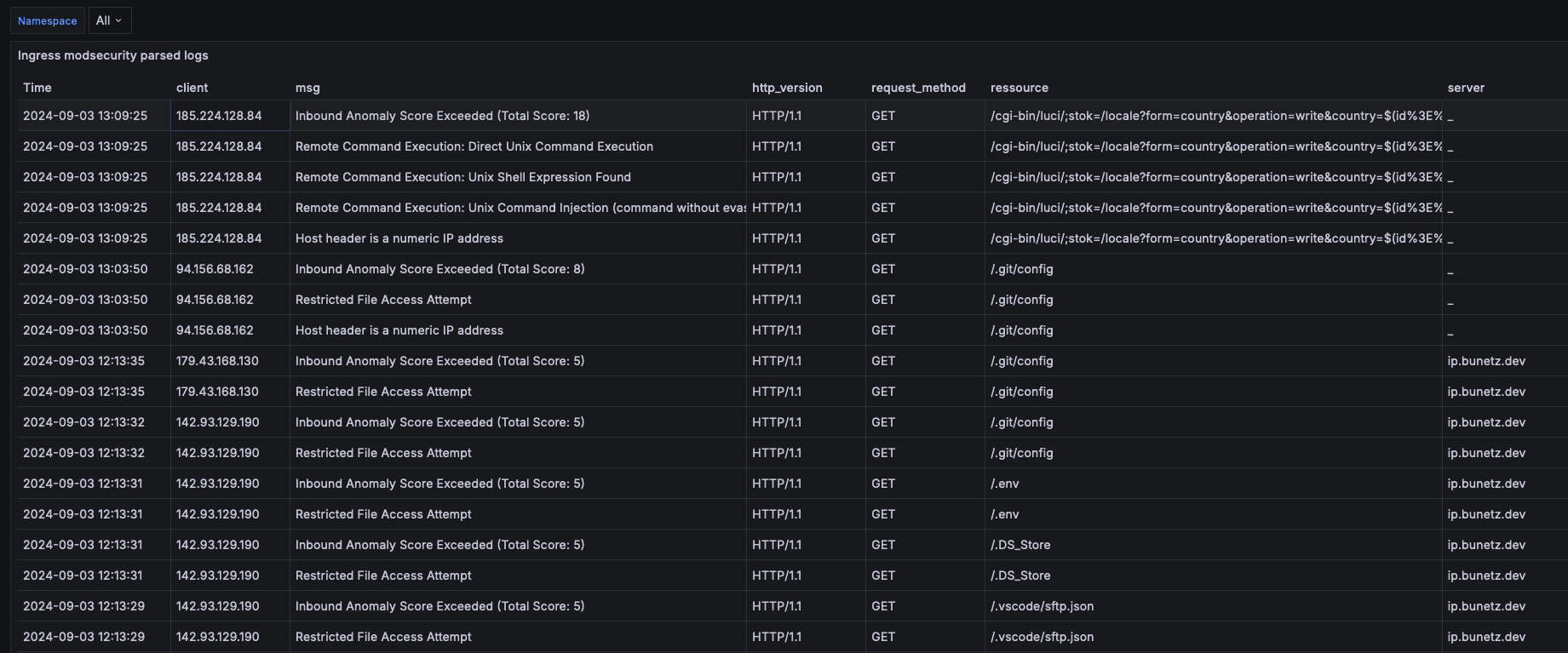

You can also create dashboards out of Loki sources. For example, I created a dashboard to get information about requests blocked by the WAF. To do this, you can parse the ingress-nginx log lines which contain ModSecurity: using this query:

{namespace="ingress-nginx"} |= `ModSecurity:` | pattern `<date> <time> [<level>] <_> <_> ModSecurity: <modsec_action> [file "/etc/nginx/owasp-modsecurity-crs/rules/<rule_set>.conf<_> [id "<rule_id>"] [msg "<msg>"<_>[ver "<owasp_version>"]<_>, client: <client>, server: <server>, request: "<request_method> <ressource> <http_version>"<_>` | __error__=``

You can also simply search using {namespace="ingress-nginx"} |= `ModSecurity:` to see the raw log lines and easily identify which rule is being triggered, so you can easily whitelist it in case it is a false positive.

That’s all for my monitoring setup. I hope you found it interesting. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions!

I am running multiple services for a variety of reasons. Here is a summary:

ArgoCD: for deploying my services using GitOps.

Bunetz: my personal blog.

Cert-manager: for issuing and renewing SSL certificates using Let’s Encrypt.

Grafana: for monitoring and alerting.

Ingress-nginx: for exposing services to the internet.

Longhorn: for distributed storage.

Prometheus: for metrics.

Sealed Secrets: for storing secrets in Git.

Homebridge: for controlling my smart home devices which are not compatible with HomeKit.

Immich: for saving and backing up my photos. A very good replacement for Google Photos.

Loki: for logs.

Myst node: for running a Myst node and earning passive income by sharing my bandwidth.

Pg-backup: a custom service I created to backup my PostgreSQL databases.

Pi-metrics: a custom service I created to get temperature data from my Raspberry Pi’s and export it as metrics.

Pi-hole: for blocking ads and tracking on my network.

Postgres: database for all services which require a database (grafana, immich, …).

VaultWarden: open source Bitwarden implementation.

Whoami: a simple service which returns the IP of the client calling it.

Public-ip-server: a simple service which figures out the public IP of my Raspberry Pi and returns it so I can use it in automations to SSH into my Raspberry Pi from anywhere.

I added simple configurations for each of them in the repo, so you can use it as a reference if you want to set up any of these services.

The only service which is a bit different because it has some configuration which is external to Kubernetes is Immich. In order to store its data, I use a local persistent volume, but I didn’t want to just store the data unencrypted, since if someone would steal my Raspberry Pi, they would have access to all my photos. For this reason I created an encrypted folder in my Raspberry Pi using fscrypt. This ensures that all my photos are stored on my hard drive encrypted and the only way to access them is to log into my Raspberry Pi and mount the encrypted folder. I also made the Immich startup command check if the encrypted folder is mounted, and if it is not, it will not start the service. This way I ensure that Immich will found an empty folder and assume that there is no data. This folder is also backed up, but I will explain the backup strategy in the next backups and disaster recovery section.

Backups and disaster recovery are crucial for any system. I had to learn the hard way what is important to backup in this system when one of my SD cards kept getting corrupted and I had to reset the cluster from scratch multiple times. Thankfully the cluster was barely alive and I could recover some imporant things which I was not backing up. First I will explain the simple backup strategy of my data and then I will explain the disaster recovery strategy which includes the backups of other not straightforward things.

Backups

There are multiple things which are important to backup. First of all, the most obvious: databases. I created a simple service called pg-backup which is a simple PostgreSQL backup service. It uses the pg_dump command to dump one or more databases into files with timestamps and delete the old ones. It also provides metrics to be able to set up alerts in case backups fail. This service also uses a Longhorn volume to store the data.

Logically, the most critical part to backup are the Longhorn volumes. Luckily Longhorn already offers backup solutions, so I set up backups to Azure blob storage. After this, it’s just a matter of using the GUI to decide which volumes are backed up and which are not.

Lastly, the last thing I’m backing up is my Immich photos. For this I’m also using Azure blob storage, but since this is not a Longhorn volume, I set up a Kubernetes cronjob which uses rclone which to sync the whole folder with encryption by mounting a configuration file saved in a secret.

Disaster recovery

At first, I believed that just backing up my data would be fine and I would be able to recover from any disaster. This is far from true, since for example, what can I do with my vaultwarden database volume if I don’t have the password for it? or how do I recover my photos if the encryption password is in a sealed secret? For this reason it is very important to also back up all the secrets and passwords. Also, if you want to make your life easy, you should back up the encryption keys for the sealed-secrets controller. That way you won’t need to reencrypt everything. For these 2 purposes I provide 2 simple scripts: one which will help to decrypt all the secrets so they can be kept somewhere safe, and another one to backup the encryption keys so you can recover them in case of a disaster.

Another nice thing to backup is ArgoCD configuration. I really don’t want to have to add all my services from scratch to Argo, so you can run a script which will dump the configuration of Argo CD to a file which can be imported later. I added a script for that as well, but it’s just a really simple command which can be found in the ArgoCD documentation.

When all this is backed up, restoring the cluster once you have an empty cluster is quite simple. First of all, you need to install ArgoCD, and then restore its configuration. You should then restore the sealed secrets keys using kubectl apply -f main.key and then sync Sealed secrets so it will be initialized with the old keys. Then you need to sync Longhorn and start restoring the backups. Once the backups are restored and sealed-secrets has the keys required to decrypt the secrets, it should be just a matter of syncing the ArgoCD services and you are good to go again!

Conclusion

Thanks a lot for reading this post and giving any feedback! I hope that, once again, this post will be useful for someone who trying to follow a similar journey to mine. Please, do not heasitate to let me know any issues you find in my setup, suggestions or questions. You can reach me over on Reddit or whatever platform I list on the about me section of my webpage.

Thanks for following along! 🚀